'Radical Imagination, Radical Listening'

Jordan Seaberry, RWU Law Class of 2020

Master of Studies in LawFor artist and community organizer Jordan Seaberry ’20 – co-director of the nonprofit U.S. Department of Arts and Culture – earning a Master of Studies in Law degree from RWU Law was a key that helped him weave together the two seemingly disparate threads of his professional life.

“In the trajectory of my own work, this really feels like the first time I have really blended the arts and social justice work together,” he says.

The Chicago native first stepped into the life of a community organizer a dozen years ago, when he dropped out of Rhode Island School of Design – which had originally brought him to the Ocean State – and began working on prisoners’ rights.

“I was starting to understand the issues around race, class, gender, access, things like that,” he explains, “in ways that, weirdly, I hadn’t picked up on before – despite growing up in a city like Chicago, which is deeply segregated along racial and class lines. I felt really overwhelmed and I didn’t know how to plug my art into those issues. So, I left – I dropped out of RISD.”

But he remained in Rhode Island, taking a staff position at DARE (Direct Action for Rights and Equality) in Providence, where he directed a criminal justice campaign.

“That’s where I learned how to write legal language, how to draft legislation, get bills sponsored and move through the lobbying process,” he said.

After two and a half years without touching a paint brush, Seaberry returned to RISD, where he set to work translating his legislative efforts onto canvas. “I realized that at the end of the day, I was shortchanging my community,” he said. “And I was shortchanging myself by not figuring out a way to blend these two sides of myself together.”

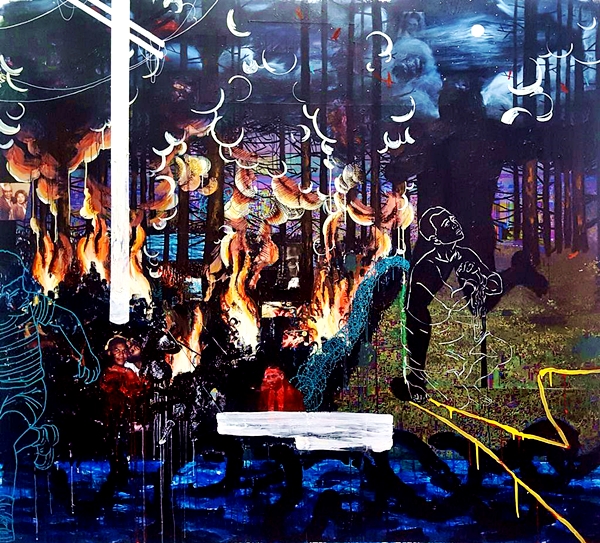

In 2019, his first solo show, “We Speak Upon the Ashes,” was presented at the Steven Zevitas Gallery in Boston, drawing excellent reviews. The Globe noted that Seaberry’s “large-scale, imagistic mixed-media paintings address systemic injustice, family wounds, and moving forward.”

Seaberry, who was by then working as a director of public policy at the Nonviolence Institute in Providence, said the thoughtful, engaged reaction his art provoked was largely the point.

“Every painting in that show was directly related to, or in conversation with, one of the social justice civil rights movements happening in Providence right at this moment,” he explained. “So folks at the gallery would see the paintings, know what campaign they were in conversation with, and at the same time get directly plugged into some of the work.”

After years of working for grassroots legislative reform, Seaberry said he’d begun to appreciate “the impact lawyers have on the political process and how they define the society.” Researching ways to deepen his legal knowledge, he eventually discovered and enrolled in the MSL program at RWU Law.

“Community organizers typically start at the legislative level,” Seaberry said. “We are trained in the ‘Schoolhouse Rock!’ style; that is, if you want to change the law, you start with the legislature. But being in the MSL program really opened my eyes to other possibilities, like changing the law and pushing for social justice through the judiciary. Not just the legislature, not even just the executive branch – but really diversifying our tactics and building a movement that tugs on all three branches.”

Seaberry also learned just how important it is to understand those branches “from the inside.”

“For example, there’s one bill that I worked on as a young organizer where, after about four years of fighting for it in the state house, we were finally able to pass,” he recalled. “But in the meantime, opposition groups had managed to pass innumerable tiny little bills that seriously undercut our bill’s effectiveness. And so by the time we finally won passage, some of the teeth had already been taken out of it. For me, that sent a really clear message that, while we had won the policy battle, we’d lost the larger, cultural battle.”

The MSL program helped him learn to bridge that gap.

“I remember, in Criminal Law with Professor Tara Allen, really distinctly realizing that – though I’d been working with legislative reforms for a decade at that point – this was the first time I was really able to see how lawyers think,” Seaberry said. “Scientists, for example, look at all the evidence and then draw a conclusion. A lawyer, by contrast, already has a desired conclusion in mind and searches out the evidence that supports the case they want to prove. For me, being able to understand that from the inside changed how I thought about organizing.”

That realization changed his approach.

“When I think about my role now – where I am trying to plug 30,000 artists and educators and union folks into a social justice movement – I know that my task is about more than just winning political battles,” Seaberry said. “It’s also, in many cases, about being able to go toe-to-toe with legal theories. Thanks to the MSL, I can now understand where those political minds are coming from and how those decisions are getting made. And I can either support and advocate for them, or I can stand more strongly in opposition, with what I think is a stance of radical imagination and radical listening.”